From: Socialist Worker

Interview: Marjane Satrapi

In March, the critically acclaimed graphic novel Persepolis made headlines in Chicago--but not for the reasons you might think.

The book is an autobiographical account by Marjane Satrapi about growing up in Iran during and after the Iranian Revolution--and her flight to live in Europe after the post-revolutionary regime became more repressive. Chicago Public Schools (CPS) officials ordered Satrapi's book pulled from the shelves of school libraries. Administrators reportedly not only required that the book be pulled from libraries (which is against the law) and classrooms, but they ordered that it not be taught in class.

After an outcry by teachers and students, CPS CEO Barbara Byrd-Bennett backtracked, issuing a letter in which she denied the district had banned the book, but maintaining the order that it not to be taught in the seventh grade curriculum because of its "graphic images."

In this interview with SocialistWorker.org's Khury Petersen-Smith, Satrapi spoke about her feelings on the Chicago controversy--and the importance of literature and education in challenging the status quo.

The book is an autobiographical account by Marjane Satrapi about growing up in Iran during and after the Iranian Revolution--and her flight to live in Europe after the post-revolutionary regime became more repressive. Chicago Public Schools (CPS) officials ordered Satrapi's book pulled from the shelves of school libraries. Administrators reportedly not only required that the book be pulled from libraries (which is against the law) and classrooms, but they ordered that it not be taught in class.

After an outcry by teachers and students, CPS CEO Barbara Byrd-Bennett backtracked, issuing a letter in which she denied the district had banned the book, but maintaining the order that it not to be taught in the seventh grade curriculum because of its "graphic images."

In this interview with SocialistWorker.org's Khury Petersen-Smith, Satrapi spoke about her feelings on the Chicago controversy--and the importance of literature and education in challenging the status quo.

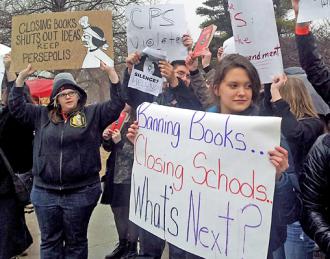

Students at Lane Tech High School protest the banning of Persepolis

Students at Lane Tech High School protest the banning of Persepolis

FOR PEOPLE who haven't read it yet, could you describe Persepolis briefly and give us a sense of your reaction to the controversy in Chicago?

IT IS based on the story of my life. Of course, like in any book,

it's also a story, and in order to write any story, you need to make it

fluent. But it is based on the story of my own life: the way I grew up

in Iran, and the revolution that happened, and when the war happened.

My whole goal was to say, as an individual, as a person: How do you

grow up in these many regions of the world? How do you deal with

dictatorship, how do you deal with war, and how, in the middle of it

all, do you just try to make a life as normal as possible? What is

exile? All these questions.

I had also had enough of the fact that, for many, many years, Iran

was portrayed as evil--as part of the "axis of evil." I think that from

this, you forget that human beings are just human beings. You are told

instead that these people just hate the West, and all they want to do is

kill themselves in war.

As soon as you make an abstract notion about people, it's easy to go

and bomb them and destroy them, because they have stopped being human

beings. So my whole goal was to give the other understanding, one that

wasn't in the mass media, and another point of view. This was my point

of view, because I was sick of hearing that all Iranians are like this

and like that.

It wasn't the other point of view, because I don't consider myself a

politician or a sociologist or something like that. Basically, it just

happened that I was born in a certain place, in a certain time, and I

thought it was very important to give at least another point of view on

the story.

Really, the best response I ever had to the book was in the United

States, because people there were very eager and almost hungry to have

all this information. It was so good to see that this book has been

taught in the colleges and high schools, and that if you're a kid, you

can ask yourself these kinds of questions. It's easier to grow up in a

better way than if you discover these things when you are 52. That's a

little bit late.

So that's why this whole story in Chicago was absolutely shocking to

me. They're saying it's inappropriate for kids because of the scenes of

torture that were in just a couple of frames--in a book that is 200

pages long!

It's as if children never killed anybody in their video games, or as

if they had never seen any films that contain violence. As you know, in

America, kids can watch violent movies, and it's not a problem, but if

you say the word "fuck," that is unacceptable. Children are exposed to

violence. But if it's the violence of guns on TV, that is accepted.

Chicago Public Schools doesn't like the "pictures of violence" in my

book, but there are no pictures. This is a description. These are

drawings.

Also, it's based on the story of my life, so it's not some stuff that

is made up to make kids scared. These things exist in the world. It

takes place everywhere. It even exists in the United States. Torture and

prison--these are human realities, and if you are aware of them, then

maybe later on, we can fight them. Because you understand the horror of

this situation.

It can help you grow up and maybe think in another way. If you don't

expose your children to this--if your children are in seventh grade, and

you're still talking about Mickey Mouse and Donald Duck--that isn't

normal.

The worst part is they say that they haven't banned the book, but

each teacher who wants to teach it will have to get some kind of

guidance. That means they make it difficult. If I'm a teacher, and I

have to go get guidance to teach a book, then I will teach another book.

This is just another way of banning it.

For me, the biggest insult is to the intelligence of the teacher.

Becoming a teacher in America is a vocation. If you go to college, and

you want to make money, teaching is not really the best choice. People

don't become teachers because they say, "Oh cool, I'm going to make big

bucks." They become teachers because they're committed to educating

people.

Especially in public schools, these are people of conviction. They do

that because they want to help children. And the officials are telling

them that they have to have guidance--that they're a teacher and they

don't know how to teach the thing.

What is so horrible in my book that you need guidance? Am I inviting

people to go find a shotgun and kill each other? Am I teaching the kids

to hate the other ones? Am I teaching them to be violent?

No. What I'm telling them is that the world can be like that, but in

the middle of this bad world, we can always choose another way. We can

always not hate. I think this is good for kids to learn, and the earlier

they learn these things, the better. So this is extremely shocking.

And I think it's even more shocking that it comes from Chicago. This

isn't like someplace where you can't study Darwin because "Adam and Eve

made us." It's Chicago! It's supposed to be a liberal city!

It's very bizarre, because in the beginning, they said: Go and take

all the books from all the libraries. And then they said: Oh no, we

didn't say that, we just wanted the teachers to have guidance. Because

teachers don't have any brains, they don't know what they're doing, so

they need some guidance to teach a book that is a comic book and is

extremely clear about what it is saying to the kids.

YOUR BOOKS portray Iranian people and society with

this rich nuance--as a place with real people, where people made real

decisions. That seems to be incredibly important for young people to

learn, especially in the United States--where what we learn about Iran

and the Middle East is often the opposite.

ABSOLUTELY IT'S important. If we don't want more wars to happen, then

we need knowledge of the others who we're told to kill. If I don't know

Americans, then I can hate them. But if I get to know Americans, and

they become my friends--if I think they are like me--then I would have a

problem going and killing them, like any population in the world.

So I think these are good things to learn. And I really don't know

what the hell their problem is. I think it's extremely shameful that

they lie this way. That they say they didn't ban it, but they did

everything they could to make it impossible to teach. Or that

seventh-grade kids are "too young." I mean, come on! We are in 2013!

I THINK this is a very typical thing in the United

States--to say, oh we aren't going to ban it outright, but then to

create restrictions that make it impossible, like you said. You may know

that there's a struggle in Chicago over education justice--in a system

where, actually, 160 public schools don't have libraries.

I KNOW! After they removed the books from the curriculum, they said

it was available in the libraries. So what do we do for the 160 schools

that they don't have any libraries?

I've been to the public schools in Chicago. I know that these kids

don't have any access to anything special--because, of course,

everything revolves around the money.

I received so many thousands of letters from American kids that gave

me hope. The typical way young people are presented is that these are

people with no brain, no pain--that they're on Facebook all the time,

and oh my God, they don't think anymore! They're text messaging the

whole day!

But then you receive these letters, and you see that, no, they're

bright, they're intelligent, they're curious. They want to know, and

that gives me hope. I think: Cool, this is another generation that is

going to rise up, and maybe they'll do better than we did. It is

possible.

YOU'VE BEEN speaking from a place of tremendous

respect for young people and for teachers to be able to think for

themselves with these books that you've written. That seems to be a very

different attitude from the Chicago Public Schools administration.

OF COURSE children have a mind, they have a point of view. They are

extremely curious, and they want to know lots of things. And teachers--I

have tremendous respect for them because this is really not a lucrative

job, and yet they choose to do it.

I have been saved in my life because I had some great teachers who

trusted me. At a time that I was completely lost in my life, I had a

couple of teachers like that, and if they weren't there, maybe I would

have been dead by today. So, of course, I have a great respect for them.

And then come these bureaucrats, and they say, "These people for this

semester at this school don't like the book," and two parents say, "We

don't like this book." What about all the other parents and all the

other high school principals and teachers who did like the book? What about them? Should everybody be punished because two people said they don't like it?

At the same time, they say they're defending freedom of speech and

banning a book-- and then they lie about this and say they didn't ban

it.

That is such a big hypocrisy. I would prefer if they said, "We hate

the book, and we don't want to teach it." Then it's easy. At least they

have to be straightforward.

DO YOU know of any other places where your books have been banned or censored?

YES, BUT only in dictatorships! This is where the book is banned!

It's a book that says, think for yourself, make your own decisions. So

of course under dictatorships, they don't like that kind of things.

But really, in the United States of America, which is supposed to be

the world's leading democracy. They're going everywhere in the world

making war, and saying that they're defending "democracy" and freedom of

speech. But there isn't a freedom of speech in America.

AS SOMEBODY who has lived under more than one

repressive regime, can you talk about the importance of freedom of

information and art and literature?

OBVIOUSLY, THE more you know, the more knowledge you have and the

more free you are. The more you understand the complexity of the world,

the less you become violent, because you understand that "enemies" may

be somebody like you. The more you are cultured, the more it's easy to

have correspondence with other people from other countries.

We're always very scared of the thing that we don't know. That is the

nature of human beings. So the importance of knowledge is big. If our

policies fail--if they're achieving the wrong results--the solution is

more education.

Around 120 years ago, Peter Kropotkin, the anarchist, said that if

you want to construct fewer prisons, you have to construct more schools.

I really truly believe in that. I believe in education. I have total

respect for the younger ones, and for the teachers.

DID YOU hear that some high school students at one school in Chicago organized a protest against the censorship?

I KNOW! I saw the pictures. I was extremely proud of them. I thought

that was awesome, and not because it was my book. It could have been

another book, and I would have been just as proud.

IS THERE anything else you would like to say to

students in Chicago, or to teachers, or to the administrators who made

the decision to censor your book?

TO THE administrators I would say: Find your brain again. Stop lying,

stop being hypocritical, and trust the young people. Read the book

first and don't just be shocked by one picture. Read it first, and then,

if you really are shocked, don't teach it. But I'm sure these people

didn't even read it.

I would say to the children that I trust them--and I really trust

that they will make a better world. I think they are very intelligent,

and I really believe in young people.

To the teachers, I would say that I respect them more than anyone in

the world because this is really not an easy job to do. Thanks to people

like them--they saved my life.

No comments:

Post a Comment